Teaching Philosophy

My pedagogy is committed to the liberal arts virtues of critical thinking, diversity, equity, and inclusion; intellectual exploration; practical wisdom; and civic engagement.

Today’s students have lived through a once-in-a-century global pandemic; economic upheaval; climate change; racism, sexism, homophobia, and transphobia; hyperpartisanship; increasingly prominent artificial intelligence; pervasive social media; unceasing gun violence; and more. These and other civic issues necessitate educational approaches that prepare students to respond to this complicated environment. A liberal arts education—one anchored in practices such as critical thinking and problem solving, ethical and inclusive perspective building, civic engagement, and sustainability—is especially suited to such a moment. My courses are undergirded by these approaches to a liberal arts education. I utilize a combination of theory and practice, as well as lecture, discussion, and application, in order to educate students in the fields of rhetoric, communication, media studies, and leadership. I work to create a safe space of intellectual inquiry for my students, and I believe strongly that students should be taught through multiple methods and assessed through a variety of assignment types.

I utilize a combination of lecture, discussion, and application in my courses.

My classrooms are, first and foremost, spaces of critical inquiry and intellectual exploration. I utilize a mix of lectures, usually between 15-30 minutes in length, and discussion, case study work, and other forms of collaborative learning. I supplement lectures with a combination of slide decks, participatory technological tools such as Mentimeter and Kahoot, notes on the board, handouts, and embedded examples (videos, images, charts, passages from an assigned text, etc.). These materials, in conjunction with the lecture itself, provide students with ample opportunities to take notes. In each course, regardless of level, I facilitate student discussion of course content, including assigned readings and examples provided in lecture. Discussions tend to be shorter in my 100- and 200-level courses. In 300- and 400-level courses, such discussions are the primary modality for student engagement with content. Alongside and in support of both lecture and discussion, my courses include opportunities for student application of content through case studies, analysis of communication artifacts, and other forms of media engagement (e.g., playing video games, listening to music, watching television). This diversity of modalities better captures—and holds—students’ attention and provides them with repeated opportunities to both learn content and put it into practice.

My courses help students to develop problem solving skills as well as to critically reflect on issues of community concern.

My courses help students to develop problem solving skills as well as to critically reflect on issues of community concern. This is especially evident in my COM 217: Video Games and Contemporary Problems course. Students collaborate with their peers as part of three long-form video game labs (five weeks each, 75-minutes per week) and shorter in-class labs deemed “free plays” (40-45-minutes, sessions distributed across lecture and discussion sessions. These labs provide students with concrete opportunities to solve problems, learn from failure, and develop their skills in interpersonal communication and teamwork. Moreover, course labs help students engage with civic issues such as health care (Firewatch), the ethics of city construction and infrastructure (Cities: Skylines II), debt (Animal Crossing: New Horizons), economic insecurity (Night in the Woods), and borders and immigration (Papers, Please). Building from course readings and these applied lab experiences, the course concludes with a creative project that tasks students with composing and pitching a video game designed to assist players in better analyzing, understanding, and solving a substantial problem facing their community.

My courses facilitate students’ development of multiple communication skills, including those in small-group discussion, video conferencing, formal presentation, interpersonal communication, organizational communication, debate, and deliberation.

I facilitate students’ refinement of multiple communication skills, including those in public presentation, video conferencing, debate, deliberation, small-group discussion, interpersonal communication, and organizational communication. Such skills are imperative as students prepare to embark on a wide variety of careers upon graduation. Moreover, they are pivotal as students engage in community work, as they negotiate complex family dynamics, and as they participate in public life. For instance, my LDR 215: Digital Leadership course includes two communication projects. The first tasks students with developing a profile of a digital leader; this profile is delivered via Zoom. The second, building upon the first presentation, invites students to complete mock job interviews via Teams. These assignments introduce students to, and provide a space for refinement of skills in, professional communication on two of the most widely used video conferencing platforms. Likewise, three of my courses, COM 211: Sports, Media, and Culture, COM 308W: Communication and Media Ethics, as well as LDR 215, include student debates. Alongside substantial units in argumentation and reasoning, these assignments give students the opportunity to craft, question, and evaluate arguments related to civic issues in sports, ethical, and digital contexts, respectively. Additionally, my LDR 315: Diversity and Leadership course is anchored by a semester-long deliberation project. This group assignment gives students an opportunity to brainstorm, research, organize, and facilitate a community deliberation on campus related to an issue facing the Eureka College community.

My courses assess students through a diversity of assignments, projects, and other demonstrations of learning.

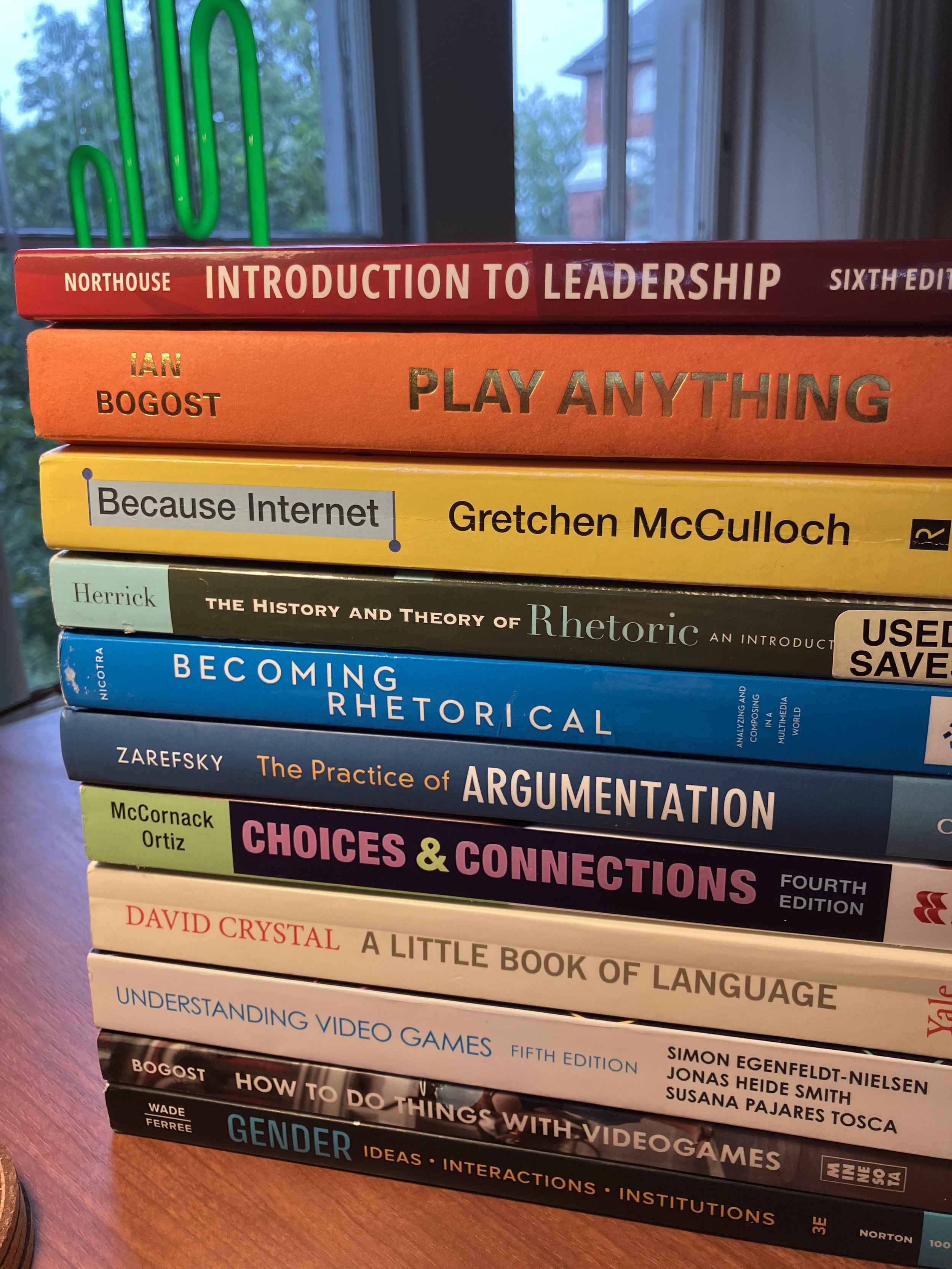

I assess students through a diversity of assignments, projects, and other demonstrations of learning, including presentations, daily homework, quizzes, exams, in-class writing, long-form research essays, one-on-one meetings, individual and group projects, reading assessment, and assessment of in-class engagement. My courses also position students to develop long-term understanding and knowledge of course content. Students are exposed to information multiple times: first through reading or engagement with other assigned media (including television, as in my COM 215: Relational Communication course; music, as in my COM 108: Media and Culture course; and social media, as in my COM 213: Social Media and Internet Culture course); second, through in-class discussion and lecture; third, on a quiz; fourth, through the correction of quizzes; fifth, through the completion of shorter writing or presentation assignments; and, finally, on a cumulative final exam or as part of a final research essay or project. This approach to student assessment provides opportunities for regular feedback, for student growth, and for the development of long-term knowledge and applied skills related to course content.

I take seriously the notion that my pedagogical development is a career-long effort of trial and error, success and failure, and learning from both my students and colleagues.

I work to incorporate student feedback as relayed through end-of-semester course evaluations as well as through informal conversations about students’ experiences in my courses. I also regularly seek out feedback from colleagues about new assignment ideas, course redesigns, new course proposals, and more. Such opportunities for pedagogical reflection and innovation are invaluable and are one of the primary reasons that I have chosen to build my career at small liberal arts colleges. My nearly decade of experience in liberal arts education has instilled in me a firm commitment to the necessity of ongoing pedagogical development. My teaching philosophy, as detailed above, reflects this commitment to providing educational opportunities that are both student-centered and anchored by a liberal arts approach to rhetoric and communication.